Assessing Service Needs: The Modelled Survey Approach

The modelled survey approach provides a transparent, cost-effective and statistically robust method of building strength into carefully structured local surveys.

This approach rests on modelling individual- and area-level survey data and applying derived parameter values to the known characteristics of local populations (as derived from the 2001 Census). Adopting a multilevel modelling framework, this enables acceptable estimates of local service needs to be generated using much smaller sampling ratios than have hitherto been necessary. Moreover, by implementing the approach using recently developed Bayesian statistical techniques means that the reliability of the local estimates can be explicitly defined — encouraging a nuanced and realistic interpretation of the data.

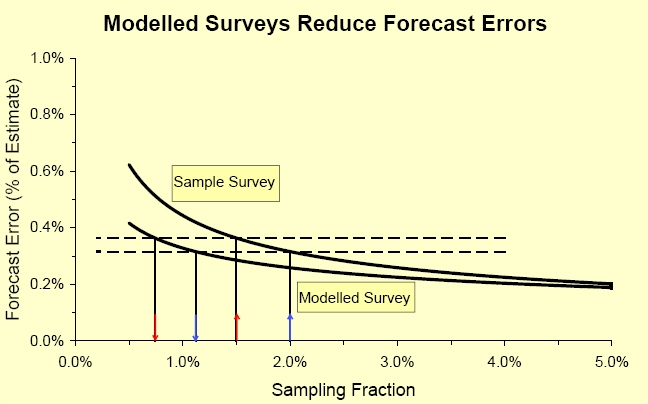

As illustrated below, substantial improvements in Forecast Errors[note] can be achieved by adopting a multilevel modelled approach. In this example, which concerns the prediction of adult smoking rates in 31 'pseudo wards', a sampling fraction of only 1.1% in a multilevel modelled approach achieves the same forecast error as would be obtained using a 2% sampling fraction in a simple sampled survey approach. Given that the cost of implementing a survey is largely determined by the number of individuals surveyed, in this instance adopting a modelled survey approach nearly halves costs relative to traditional sampled surveys.

Moreover, as illustrated below, the larger the acceptable Forecast Error the greater is the 'value added' through multilevel modelling. Thus in this example, to obtain a relative Forecast Error of 0.36% requires a sampling fraction of 1.5% using a standard survey but only 0.75% when a multilevel modelled approach is adopted.

Whilst a modelled approach will always improve the predictive power of a survey, the precise 'savings' that can be achieved vary from case to case. Clearly, as illustrated above, the smaller the sampling fraction the stronger the argument for adopting a modelled approach, but the strength of the relationship between the target outcome measure (in this instance smoking status) and the predictor variables is also important. In essence, the stronger the social gradient, the greater the savings to be gained through multilevel modelling.

Monitoring Change

Monitoring the impact of policies and programmes has always posed a significant problem for service providers. Invest too much on evaluation and the capacity to implement effective policies and programmes is compromised - invest too little and it is difficult to judge which policies and programmes are actually effective.

Adopting a modelled survey approach goes some way to addressing this problem because it brings down costs to such an extent that a series of surveys can be justified. For instance, remaining with the example of adult smoking, whilst hospital admission and other health indicators will eventually reflect the effectiveness of smoking cessation policies and initiatives, these data are of no value in policy development or programme evaluation. Only through a series of lifestyle surveys is it possible to obtain 'real-time' empirical data on changes in smoking behaviour in different areas and thus possible to judge the effectiveness (or otherwise) of current policies and programmes.

Thus although traditional sampled surveys are invariably too costly to justify on a regular basis, PCTs and their partners could readily implement a programme of periodic 'modelled lifestyle surveys' (MLS) as the basis of an empirical assessment of the impact of their policies. MLS are able to deliver statistically significant estimates regarding the prevalence of health risk behaviours at a fraction of the cost of a traditional lifestyle survey, though the need to collect local survey data means this approach is still more costly than synthetic estimation.

Synthetic estimation offers a means of benchmarking the public health needs of populations without recourse to local surveys, but it cannot be used to mointor change. MLS can be used to monitor change and, because it is based on bespoke local surveying, can be tailored to meet the specific needs of the client whilst simultaneously fulfilling the stringent requirements of post-survey statistical processing. Finally, MLS can be explicitly embedded within the local evaluative framework – enabling PCTs and their partners to focus on specific interventions and their impact on the public health of local communities.